I

SEE myself as a deeply-perusing observer. Meantime, my reflex usually

veers away from taking sides—and opts for reason and wisdom even

beyond my own convenience. I'd like to say that as backdrop to my

(continuing) observation of China—a consuming thesis that dates

back to my childhood. The Chinese has always perplexed and mystified,

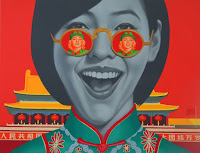

intrigued me. From the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 and Deng

Xiao Ping's ushering of Beijing's economic open-door policy to the

hubbub that it sent to World Trade Organization at Bill Clinton's

administration (remember the Battle of Seattle?) to Foxconn's clout

to the South China Sea tempest etc etcetera.

The

Chinese are a kind of humanity that don't talk much. They just work

and deliver what you want. Reject it, they'd complain less—and

quietly leave. After sometime, they'd show up with a new prototype or

alternative until you are convinced. When they fall into silence or

sleep, don't settle—they are actually (re)planning things out.

For

years since the huge nation's WTO entry in 2001, the Chinese

economy's expansion has been relentlessly breakneck. As provincial

entrepreneurs enjoyed Beijing's subsidy, rapid development has

turned fishing villages into factory towns and factory towns into

financial hubs. But that's not all heaven. “Heavy investment has

crowded out consumption, and heavy industry has muscled out services,

as if making stuff mattered more than serving people,” The

Economist writes. China's socialism/communism's interface with

Western-styled capitalism has somehow shook the gains of the Cultural

Revolution's populist wisdom. But then, wait. Is that all bad? Not

really.

In

other words, China is sliding to a new phase of its march to modern

times, Western-style. From manufacturing, Beijing sets its gears at

consumers and services, two promising trends that work around each

other. Because services are more labor intensive than industry, their

growth boosts wages and household income. Money on the hand of the

consumers. Heftier take-home pay jacks up consumption, and consumer

spending, in turn, favors services.

But

then you think China will slow down its giant manufacturing machine?

No. They are just setting sight on other options. In other words,

China is pretty much aware not to follow the mistake/s of America. As

The Economist puts it, “As China’s economy matures, its pace will

slow. Fighting this economic law will only invite inflation, excess

and harder reckonings. Growing fast is a poor alternative to growing

up.”

LET's

look beyond the mainland and check what the Chinese are up to. I am

leaving the South China Sea maneuverings on this discussion and

instead focus across continents.

Since

2008 China has agreed some $500 billion in currency swaps with nearly

30 countries, from Canada to Pakistan, which gives the counterparties

access to yuan when trouble is suspect. A currency swap is a foreign

exchange derivative between two institutions to exchange the

principal and/or interest payments of a loan in one currency for

equivalent amounts, in net present value terms, in another currency.

Currency swaps are motivated by comparative advantage, an economic

theory about the work gains from trade for individuals, firms, or

nations that arise from differences in their factor endowments or

technological progress.

Meanwhile,

Chinese banks have lent $50 billion to Venezuela since 2007.

Argentina is the second-biggest recipient of Chinese loans in South

America. Then there is Russia, who may have the largest deposit of

crude oil in the world, but its economy isn't enough to develop the

natural. Again, Chinese banks have lent more than $30 billion to

Russian oil companies.

What

does that infer? That is a loud testament to China’s remarkable

growth. And more significantly, China it seems or it appears is

setting up development banks intended to challenge the dominance of

the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Analysts

have always sounded that China is on track to surpass America as the

world’s biggest economy within a decade. These are nagging hints.

Chinese banks have been making its move continent to continent.

Let

me touch Brexit for a bit and look sideways. This is all about the

world's

major banks, of course! No surprise why UK's HSBC Holdings, top

European bank, wanted out of European Union. It's not really the

country that's bolting out per se. It's the bank. Hence, if BNP

Paribas and Credit Agricole Group rebel, then expect France to

withdraw from EU as well. And join the Chinese? Not far-fetched.

I

repeat, the Chinese

are a kind of humanity that don't talk much. They just work and

deliver what we want. They'll give `em to us. But we gotta admit it.

The Chinese have indeed gone a long way from lo meins and dumpling

soups. They have evolved into slick dudes on Brooks Brothers suits

sipping Dom Perignons in stretch limos, Ivy League-educated

assistants clutching iPads and iPhones on their beck and call. As The

Economist puts it, “The anachronistic state of global economic

governance is growing ever more glaring.” It has gone eastward.

No comments:

Post a Comment